“Mental models” are on the menu in this latest BSW market update. Looking forward, we believe it will serve us well to ground on what has moved markets in the recent past to understand what may be in store for this year and beyond. Monetary (and fiscal) policy has rarely had as big of a footprint on the market as it does now. We are going to attempt to break it down so that we can build upon the all-important subject going into 2022. If you thought markets move when Elon Musk speaks, just wait ‘til Chair Powell says giddy-up!

Looking Back at 2021

Last year was a good year to be in stocks. The MSCI All-Country World Index (ACWI), the stock index BSW uses as a benchmark, was up 18.22% for 2021. Leading this index higher were U.S. large cap stocks, up 28.70% as measured by the S&P 500. The ACWI return was tempered by emerging markets stocks that fell -2.54% on the year. It was the tale of U.S. stocks riding high on stimulative monetary policies, while emerging markets fell on the heels of China restricting policy to cool their real estate market.

Bonds plotted a different course. The Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index was down -1.54% on the year and the Bloomberg Index of intermediate municipal bonds was only up 0.53%. Much of this was due to interest rates rising throughout most of the year (bond prices move inverse to yields). Also, with the largest bond buyer (the Federal Reserve) getting ready to exit the market, traders (not investors) did not want to be left “holding the bag” so to speak. Although bond price movement resulted in negative returns for the year, clients can be assured that they have locked in positive yields to maturity within their laddered bond portfolios.

After taking the above into consideration and combining 2021 returns of stocks and bonds, most clients experienced a year of high single-digit to low double-digit returns within their core, liquid portion of their portfolios. This return was enough to clear the bar of inflation, which raised its ugly head this year and recently hit 7% annualized – the highest rate since 1983. Of course, back then, it was on its way down from a peak of 14% in 1980.

Looking Ahead to 2022

Moving into 2022, the markets are faced with a conundrum. Stock valuations in the U.S. are still close to all-time highs, the Federal Reserve is set to raise short-term rates (we can debate how much in another post), and inflation is the new elephant in the room. Speaking of inflation, we expect inflation to come down slightly this year, if only due to higher year-over-year comparisons.

The key to this year seems to be that the Fed has no choice but to fight higher consumer prices with higher interest rates. That makes this year very different than all other years post Great Financial Crisis. The Fed “put” (the notion that the Fed will rescue the market with rate cuts if it takes a tumble) may not be there this time.

This is where we believe mental models can be helpful. I was exposed to the concept of mental models when trying to wrap my head around cryptocurrencies and decentralized finance (talk about mind bending). A mental model is simply a representation of how something works. When systems and concepts get complex, it becomes difficult to keep the details organized in our brains. Models take complicated concepts and convert the minutia into chunks that can be organized and understood within a simplified framework.

Back in 1990, Charlie Munger talked about mental models as follows: “Well, the first rule is that you can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang ’em back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form. You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience both vicarious and direct on this latticework of models.”

To that end, I have attempted to create a mental model of quantitative easing (QE) and by default, quantitative tightening (QT). We all know that easing is essentially “printing money” and that tightening is taking that money back. These models will tie back to the conundrum the Fed faces.

Quantitative easing is essentially what the markets have been soaking in since 2008/2009 – except for 2018 when the Fed attempted to get rates back to some semblance of normal (they failed, by the way).

I call the mental model I have adopted for QE, “Screen Time Dilemma.”

Key Takeaway: It’s our belief that incentivizing near-term behavior may be necessary, but there is a need to balance the benefits of changing behavior in the “now” with negatively influencing mid- to long-term behavior.

Any parent/grandparent can appreciate this mental model. By giving a child access to screen time when they act out, we are seeking to change a behavior. The immediately desired behavior is peace and quiet for Mom and Dad or Grandma and Grandpa. In the long run, however, the child may not benefit from unproductive screen time. Lastly, the longer we give them screen time, the more they may suffer without it.

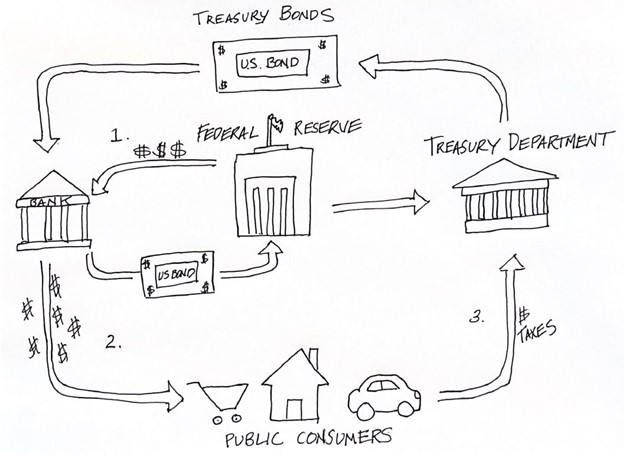

To build on this model, I’ve included a sketch diagram (almost literally back of a napkin) of how money gets into the system through QE.

- Fed “credits” bank reserves digitally in return for Treasury Bonds.

- With the extra reserves banks are incentivized to lend to consumers and businesses. Banks lend up to 10 times their reserves. In this regard, even more money gets into the system.

- Consumers pay taxes to Treasury and the cycle continues until things get too hot.

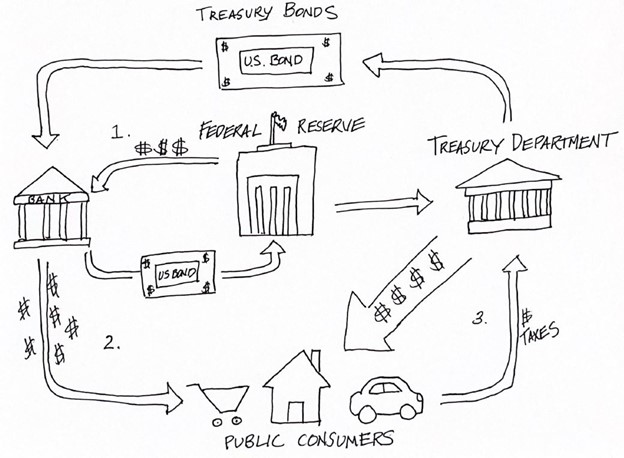

What has been different since about March of 2020, is that for the first time since the 1940s, there has been fiscal stimulus injected into the system directly by Treasury while the Fed has been easing. This came in the form of pandemic relief checks in the mail – direct to a large percentage of the population. See Sketch #2 below.

Banks can’t force consumers to borrow money and spend but give someone a check and they will typically spend (or invest in the S&P 500 as we witnessed). As expected, this caused demand for “stuff” to go through the roof. Yes, supply chains were stressed, but it was likely more a function of demand that suddenly surged way above what the supply chain could handle.

The model for QT is the exact opposite of QE. Money is taken back out of the system and other buyers of bonds need to step in and take the place of the Fed. This is typically not all bad. With the Fed slowly exiting the bond market, the hope is that the price of money (interest rates) and bond prices will more accurately reflect real world supply and demand of investors – investors that are price sensitive and should care about returns, unlike the Fed that was a giant Hoover vacuum at any price.

The worry, going back to our model, is that the market has been sitting in front of a screen for the better part of 12 years! Let’s just say the odds of a “temper tantrum” are not insignificant. This doesn’t necessarily mean a market melt-down, but during interest rate regime changes like this, things tend to get bumpy. We’ve seen this already this year. As interest rates rise in anticipation of Fed tightening, stocks have stumbled.

The other worry is that the Fed will make a “policy mistake.” In our minds, they already have. By keeping rates at emergency low levels for so long, they have made the unwind that much harder. The challenge is that for the past 12 years, companies (and the country) have been loading up on cheap debt. This debt will need to get rolled over and higher rates mean higher payments. For example, as it pertains to U.S. debt, a 1% rise in treasury yields translates to an estimated additional $225 billion in annual interest payments by the government. These are funds that get funneled away from productive uses like transportation, education, and support for those in need. At the margin, they are a headwind to economic growth.

It will be interesting to see if the Fed can walk the tightrope between taming inflation with higher rates and not causing the economy to slow too much. Inflation needs to be tamed. Inflation is a tax on everyone, but especially those who have not benefited from the rise in asset prices, i.e., stocks and real estate. A whopping 44% of U.S. households do not own a single stock, nor any real estate assets – and they vote. It’s no wonder the current administration is heavily advocating for higher rates and price controls.

As we move into 2022, BSW continues to look for investments that might offer a buffer from inflation, while also potentially zigging while the market does its zagging.

In the meantime, we are remaining disciplined and diversified and will look to take advantage of a potentially bumpier market. We’ve already built the primary shock absorbers within your portfolio – that being your target allocation between the various macro asset classes. Like exploring down a country dirt road, sometimes it’s worth the bumps to get to your destination.